There are many approaches to establishing an accurate valuation for your business. Finding the best method for your position will provide you with the best measure of value.

As you prepare to sell your business or get it acquired, you have taken several steps:

- You have examined your company’s historical financial statements.

- You have carefully considered the prospects for future growth

- You may have had your accountant recast your statements to reflect how new ownership would affect your company’s earnings and cash flow.

- You have also considered the market value of any real estate, equipment, inventory, and other hard assets that would be transferred in the sale and the intangible aspects that make your business appealing.

How do you boil all this down into an asking price for your business?

To ensure you get the best price for your business, hiring an expert business valuer is wise. The valuation process can be very complex and time-consuming. It takes quite a lot of experience to do well.

Business valuers have several valuation methods at their disposal, and even choosing the correct method (or, more likely, the correct combination of methods) to use in a given situation is more of an art than a science. The following discusses the significant approaches commonly used to put a price tag on businesses. Our objective here is to give you high-level insights into the process your valuer will go through.

Business valuation methods fall into the following categories, depending on their primary focus:

- Business assets, including book value and liquidation value methods

- historical earnings, including debt-paying ability, capitalisation of earnings or cash flow, gross income multipliers, and dividend-paying ability methods

- a combination of assets and earnings, namely, the excess earnings method

- the market for similar businesses, including comparable sales, industry rule of thumb, and p/e ratio methods

- future earnings, namely, discounted future cash flow or earnings methods

Although there is no substitute for an appraisal and valuation by qualified professionals, the value builder assessment can give you a rough idea of the value of your business.

Asset-based valuation focuses on salable parts

At a minimum, your company should be valued at the sum of the value of its readily salable parts. Two commonly used business valuation methods look primarily at the value of your hard assets.

Note: If goodwill or other intangibles are a significant component of your business, relying solely on a salable parts method could result in a severe undervaluation of the goodwill component of your business.

Book value. Book value is the number shown as “owner’s equity” on your balance sheet. Book value is not very useful since the balance sheet reflects historical costs and depreciation of assets rather than their current market value. However, if you adjust the book value in recasting your financials, the current adjusted book value can be used as a “bare minimum” price for your business.

Liquidation value. Liquidation value is the amount left over if you had to sell your business quickly, without taking the time to get the total market value, and then use the proceeds to pay off all debts. There is little point in going through all the trouble of negotiating a sale of your business if you end up selling for liquidation value — it would be easier to go out of business, and save yourself the time, broker’s commission, attorney’s fees, and other costs involved in selling a going concern. Thus, liquidation value is not even considered a valid floor for the price of your business (and you can use this argument in negotiations if you get an offer that approaches liquidation value.)

Historical earnings methods are commonly used

In contrast to the asset-based methods, historical earnings methods allow an appropriate value for the goodwill of your business over and above the market value of the assets if your earnings justify that. Although savvy buyers will be more concerned about the future of your business than its past, predicting the future is difficult. The assumption here is that your history provides a conservative indication of the amount, predictability, and growth trend of your earnings in the future.

Most companies are valued using one or more of the following methods, all of which take into account the company’s historical earning power:

- debt-paying ability;

- capitalisation of earnings or cash flow; or

- gross income multipliers/capitalisation of gross income.

The starting point for all these methods is the recast historical financials that show how the business would have looked without the owner’s or director’s salaries and perks over and above what a non-owner manager would be paid, non-operating or nonrecurring income/expenses, etc. A judgment call must be made as to whether you should look only at the last year’s statements or at some combination of statement results from the last three to five years (the most common combinations are a simple average, a weighted average that values the most recent years more heavily, or a trend line that factors in the percentage and direction of growth each year).

Debt-paying ability. This is probably the method most commonly used by business purchasers because few buyers can purchase a business without taking out a loan. Consequently, they want to be sure that the business will generate enough cash to pay the loan off within a short time, usually four to five years.

Therefore, the price must be set to entice a buyer at a point that makes this short-term repayment possible. To determine the company’s debt-paying ability, you must start with the historical free cash flow. Free cash flow is usually defined as the company’s net after-tax earnings (with a reasonable owner’s or director’s salary figured in) minus capital improvements and working capital increases, but with depreciation added back in. Interest on existing loans is usually ignored, so you start with a picture of the company as if it were debt-free.

Next, multiply the annual free cash flow by the years the acquisition loan will run. From this amount, subtract the down payment. The remainder is the amount available to make interest and principal payments on the loan and to provide the new investor with some return on investment.

Example

Your free cash flow was CUR 80,000 a year, and it is reasonable to expect the loan to be repaid in four years,

4 x CUR 80,000 = CUR 320,000.

If the down payment were CUR 80,000, then no more than CUR 240,000 (or CUR 60,000 per year) would be available to make interest and principal payments on the loan and to provide the owner with some return on the investment (CUR 320,000 – CUR 80,000 = CUR 240,000. CUR 240,000/4 = CUR 60,000).

If the owner expected a 20 percent return on this CUR 80,000 down payment, that would translate to CUR 16,000 per year, further reducing the amount available to make debt payments to CUR 44,000 (CUR 60,000 – CUR 16,000 = CUR 44,000).

An annual payment of CUR 44,000 could support a four-year loan of approximately CUR 139,474.08 at 10 percent interest or CUR 145,733.58 at 8 percent interest. Add the loan amounts to the down payment, and you arrive at a total purchase price of CUR 210,685 at 10 percent or CUR 225,000 at 8 percent. A higher price would be possible if the lender is willing to finance the deal for a longer term or a lower rate.

Capitalisation of earnings or cash flow. This is another commonly used method. Basically, it involves first determining a figure representing the company’s historical annual earnings. Generally, this is EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes), but sometimes EBITD (earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation) is used. Some buyers prefer to use free cash flow, as discussed above.

The chosen figure is divided by a “capitalisation rate” that represents the return the buyer requires on the investment in light of the market rate for other investments of comparable risk. For example, if the EBIT was CUR 100,000 and the buyer required a return of 25 percent, the capitalisation of earnings method would yield a price of CUR 100,000/.25 or CUR 400,000.

Gross income multipliers/capitalisation of gross income. Where expenses in a particular industry are highly predictable or where the buyer intends to cut expenses drastically after the sale (for example, where the buyer is already in a similar business and can centralise administrative functions), it may be reasonable to value the business based on some multiple of gross revenues.

For example, some service businesses can be valued at four times their gross monthly income. A variation on this would be to divide the gross income figure by a capitalisation rate, as with the capitalisation of earnings method discussed above.

The problem with either of these methods is that they ignore the fact that two businesses in the same industry with similar revenues can have vastly different profitability margins, depending on their expenses.

Dividend-paying ability. Some regulators listed this method as a possible valuation method for businesses. However, it is rarely used for small, closely held companies. The reason is that the ability of a small business to pay dividends is directly dependent on its earnings, so it is usually more appropriate to look at the earnings themselves. Furthermore, many small businesses try to minimise their payment of dividends for tax reasons, so looking at the company’s dividend payment record is not a good indication of the company’s value.

One situation where it may be helpful is if you are trying to sell a minority interest in the company and want to show that there has been a pattern of receiving dividends in the past. Minority interests in closely held businesses are generally complicated to sell because the investor usually can not force the payment of dividends or any other corporate decision; showing a pattern of dividend payments may be a way to make the interest marginally more marketable.

Assets and earnings valuation are often used for gift tax valuation

Assets and earnings valuation, known as the excess earnings method, takes both assets and historical earnings into consideration in arriving at the value of the business. This is the method prescribed by some regulators for estate and gift tax situations when there is no other more appropriate method. It can also be used in appraising a business being put up for sale, although the regulators might not prescribe it for this situation.

To use this method, you must first recast your historical financials to show how the business would have looked without the owner’s excess salary and perks (that is, the amount over and above what a non-owner manager would have been paid), non-operating or nonrecurring income/expenses, etc.

For the income statement, a judgment call must be made as to whether you should look only at the last year’s statement or at some combination of statement results from the last three to five years (the most common combinations are a simple average, a weighted average that values the most recent years more heavily, or a trend line that factors in the percentage and direction of growth each year). The regulators would usually prefer to see figures that represent a five-year average, which seems to be a reasonable approach.

For the balance sheet, use the most recent month’s sheet, and recast it to reflect the current market value. The starting point for your business’s value is your assets’ net value, as shown on the recast balance sheet. But how much more should you get, based on the business’s goodwill or intangible value?

Putting a price tag on goodwill. From your recast financials, you can determine your historical annual earnings figure (generally, EBIT or earnings before interest and taxes). You will subtract the earnings portion attributable to your assets alone from this. Anything left over is the “excess earnings” — the portion attributable to the going-concern value of the business.

How do you determine the portion of earnings attributable to your assets? One way of looking at this is, how much could you get if the assets were sold and the money invested at market rates? How much is the market paying for other investments of similar risks? This is one of many areas where the expertise of a professional business valuer can be invaluable.

For example, your valuer might say that, because of the risk involved in your particular business, your annual return from the current assets should be about 150 percent of the rate of a short-term government bond; your annual return from the long-term assets should be about 188 percent of the bond rate.

After you compute the expected returns from your assets, compare the total with your historical earnings figure. If the historical earnings figure is higher than the return from assets, the difference is called “excess earnings.” The excess earnings can be divided by a capitalisation (“cap”) rate to arrive at their value. Although a professional appraiser will spend a good deal of time and effort determining the proper cap rate to use, in today’s market, it will generally be around 20 to 25 percent, or enough to recover your investment in four to five years.

Example

Your recast balance sheet shows a net current asset value of CUR 80,000 and a net long-term asset value of CUR 200,000. So, the minimum or base price for your business should be CUR 280,000 — the market value of your assets.

Now let us assume that your historical annual earnings figure is CUR 150,000. How much of this earnings figure is attributable to the assets? You might calculate that under current market conditions, the return on current assets should be CUR 80,000 x 7.5% or CUR 6,000, and your return on long-term assets should be CUR 200,000 x 9.4% or CUR 18,800.

Thus, your total earnings attributable to your assets is CUR 6,000 + CUR 18,800 or CUR 24,800. Subtracting this “asset return” figure from your total earnings, you arrive at an excess earnings amount of CUR 125,200 (CUR 150,000 – CUR 24,800 = CUR 125,200).

Using a cap. rate of 20 percent, the value of your excess earnings is CUR 626,000. Add to this the current market value of your assets, and you arrive at a total price of CUR 906,000 for the business (CUR 626,000 + CUR 280,000 = CUR 906,000).

Larger companies often use future earnings valuation

Theoretically, anyone purchasing a business is interested only in the business’s future. Therefore, a valuation based on the company’s expected earnings, discounted back to arrive at their net present value (NPV), should come the closest to answering the buyer’s questions about how much the business is worth today.

That is the theory. However, in practice, valuations based on the company’s future performance are the most difficult to do because they require the valuer to make numerous estimates and projections about what is around the bend. They are also the most time-consuming methods. If inexpertly done, future earnings methods can result in a target sales price that is way off base.

Nevertheless, if you think that your most likely buyer is a larger company, having your valuer use one of these methods may be worthwhile. If carefully done by an expert business valuer, valuation methods based on future earnings can set the highest reasonable price for your business.

Methods based on future earnings are very frequently used by larger companies in either merger or acquisition situations. The large-company acquisitions manager will understand the method behind the madness of making so many predictions. Moreover, large companies are often “strategic buyers” who are likely to accept a higher price for your company in any event, provided that you can justify it. That being the case, why not set the highest asking price that you can reasonably back up with mathematical formulas and pro forma (projected) statements?

Using the discounted cash flow method. How do you go about setting a price based on future earnings? The first step is to look at your recast financial statements. Working from these, your valuer will create projected statements extending for five or more years. Each year’s free cash flow will be determined (some appraisers prefer to look at each year’s earnings before interest and taxes or EBIT). These projections should not assume any significant changes by the new investor(s) since you are trying to measure the company as it exists today; the new investor(s) does not want to pay you for the value they hope to add to the company!

Once you have done this, the projected free cash flow from each year is discounted to the present to arrive at the net present value of each year’s cash flow. These NPVs are added up to arrive at the total NPV of the company’s earnings for the near future.

Tools to use

How do you compute NPV? The easiest way is to use a good financial calculator. If you do not have one or do not want to take the time to learn how to use one, our Value Builder Tools contains a simple “present value of CUR 1” table that you can use to compute the NPV of your cash flows.

The key here is deciding which discount rate to use. The higher the rate, the lower the answer you will get as to the company’s value. The discount rate must reflect the valuer’s best guess as to what the market rate will be for investments of a similar nature over the next five years. It should also factor in the investor’s expected cost of capital (i.e., the interest rate on an acquisition loan) and the expected inflation rate. Choosing the correct cap rate is perhaps the most challenging task the appraiser must do — and perhaps the most mysterious to the rest of us. Let us say that expertise in this area is one of the main things you are paying your valuer for.

The next step in using the discounted cash flows method is to determine the residual value that the company will have after the five (or more) years of your projected statements. There are several different ways of doing this, more or less precisely.

One of the more straightforward methods is to take the estimated cash flow from the last year you have forecasted and assume that the cash flow level will continue indefinitely into the future. This is a rather conservative prediction because most buyers will want the company to continue to grow after the next five years! But, at any rate, you can take the last projected year’s free cash flow, divide it by the discount rate, and arrive at the company’s perpetuity earnings value. This value becomes the company’s residual value, which can, in turn, be discounted to find its NPV.

Finally, the NPV of cash flow from each projection year, plus the NPV of the company’s residual value after these years, are added up to arrive at the present value of the business.

Example

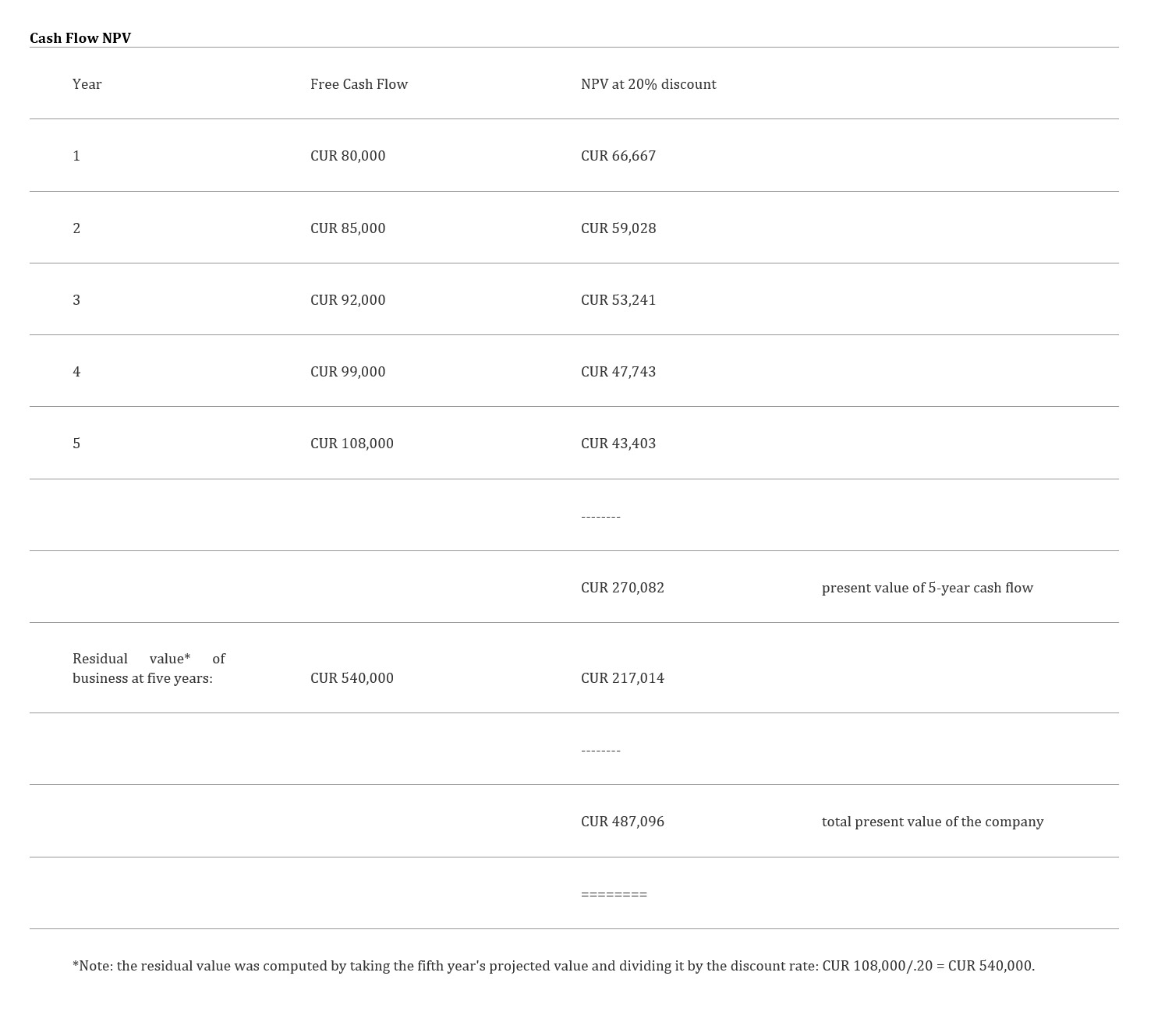

Let us say that after doing your best to look into the future and forecast the next five year’s cash flow, you arrive at the figures in column one. Assuming a 20 percent discount rate, you come up with the following figures:

Cash Flow NPV

Merger specialists favour market-based valuation methods

Several business valuation methods are based primarily on the market price for similar businesses at a given time. Business brokers and mergers and acquisition specialists are more likely to favour these methods as benchmarks since they have access to recent sales and merger activity data. Ideally, market-based methods should be used in conjunction with examining earnings (historical or projected) to serve as a “reality check.”

Comparable sales method. The comparable sales method attempts to locate similar businesses that have recently sold in your area and uses those comparable sales figures to set a price for your business, adjusting appropriately for differences. While widely used for real estate sales, this method is challenging to apply to business valuations because of the problems in gathering information about business sales and the unique character of each business.

Rules of thumb/industry averages. Business brokers frequently use these based on their experience and published standards for their industry. For example, your broker may tell you that your type of business has been selling for about four times the gross monthly revenues.

However, a rule of thumb does not consider any of the factors that make your business unique and using one can result in setting a price for your business that is way too high or too low. Nevertheless, small businesses are often sold at a price based on the rule of thumb, simply because it is a relatively fast, cheap method to use and because it will result in a reasonable price to buyers who have been looking around at a lot of similar businesses.

P/E ratios. The profit and earnings ratios of publicly owned companies in your industry are widely available. They can often be used to set and compare prices for large companies with liquid stock. However, that is the point: these companies’ stock is easily bought and sold, and it is easy for any investor to buy publicly-traded stock in many different companies.

Consequently, large-company stock commands a premium (perhaps 35 to 70 percent) because it is much less risky than an ownership interest in a small, closely held company. Also, purchasing a small business will usually tie up all the buyer’s funds and prevent him from diversifying his risk. This further contributes to relatively low prices for small business interests. For these reasons, it is best not to compare the value of your small company with the P/E ratio of a large one.

Valuing partial interests in business

Our discussion of business valuation methods assumes that you are attempting to put a value on the entire business in anticipation of the sale. But what if you want to sell off just a part of the business? Or, what if you want to give away part as part of your long-term succession plan?

Minority interest discounts. In family companies, it is relatively common to have a controlling interest in the company held by the founder, with smaller blocks of stock held by the children or key employees. If the entire company is sold, laws may protect those holding minority interests and typically require that they receive their pro rata share of the sales price. Thus, if the company was valued at CUR 1,500,000, a 10 percent shareholder should receive CUR 150,000 if the entire company were sold.

However, if only part of the company is currently being sold or given away, minority interests are valued at a discount from their pro rata price. The reason is that a minority owner is not likely to have much influence on how the company is run. He can not control the board of directors, control the payment of dividends, or even prevent himself from being fired if he is an employee.

Exceptions could occur if no one held a majority interest in the company or the company bylaws specified that a super-majority vote (e.g., two-thirds) was required to take specific actions. But, in most situations, the lack of control means that the value of a minority interest on the open market is considerably less than the value of the entire company would suggest.

The regulator and some tax authorities recognise this and will allow a “minority discount” on the stock price. Typical discounts range from 20 to 40 percent, although greater discounts might be possible depending on the facts of the situation. In the usual situation, the discount is good news because it allows the business owner to give away part of the company while minimising gift taxes or to sell part of the company while minimising capital gains taxes and allowing the purchaser to buy into the business at a reasonable cost.

Since applicable tax consequences are so important whenever business interests are transferred, and since the regulators tend to examine minority interest values very closely because of the opportunity for abuse, we strongly suggest that you use the tax authorities’ rules in deciding the discounted price.

Majority interest premiums. If a minority interest gets a discount, you might think a premium should apply to a majority interest because the interest effectively controls the corporation. If you thought that, you would be right. When sold or given away, majority interests are typically valued at more than their pro rata share of the company’s value.

For example, a majority interest of 75 percent of the stock might be worth 90 percent of the company’s total value. A majority interest should never be worth more than the total company value, however, since those holding minority interests would always be entitled to something upon the sale or liquidation of the company.

If you plan to pass your business on to the next generation of your family, carving out minority interests and giving or selling them to your successors can be a good way to reduce your estate or capital gains taxes, where applicable.